Chris Thomas

The National Library of Wales sits on the crest of an escarpment overlooking the town of Aberystwyth situated on the Ceredigion coast. Surrounded by green fields, steep sided hills, and rows of scotch firs, the library commands panoramic views in sight of the blue expanse of Cardigan Bay which can be seen sparkling in the far distance.

This imposing building, constructed in the early years of the last century, stands amidst brightly coloured flower gardens. The fields next door are grazed by flocks of sheep moving silently amidst clumps of clover, furze and wildflowers creating a scene of classical pastoral calm that reminds one of Virgil:“Are these Meliboeus’ sheep?” [1] This is surely one of the most attractively located libraries in the world and a fitting place to house one of the largest collections of John Cowper Powys manuscripts and books.

You need more than a day here to make the most of all the Powysian pleasures the library has to offer as well as enjoy the many local attractions of this popular seaside resort such as spotting bottle nose dolphins in Cardigan Bay, or walking along the cliff path to Clarach Bay. You may also want to visit the ruins of the thirteenth century castle built by Edward 1 on an exposed promontory at the edge of town or take a ride on the preserved steam railway through the picturesque Rheidol valley, or travel on the main line Cambrian railway along the Dovey estuary and the Cambrian coast in sight of Cader Idris.

Just a little further afield is Strata Florida Abbey (Ystrad Filur), with its Grail like Powysian associations, located in a lovely tranquil valley. Founded by Cistercian monks in 1164 on the banks of river Teifli, Strata Florida was an important centre for the preservation and transmission of literature, religious learning, and scientific knowledge. It was a stopping place for Giraldus Cambrensis (Gerald of Wales) who came here on his journey through Wales in 1188 and stayed for three days. He described its pasturelands and the surrounding “lofty mountains of Moruge called Elenydd in Welsh”.[2] Strata Florida is also the location of a modern Grail myth where a small bowl made of wych-elm, the ‘Nanteos cup’, reputed to have magical healing properties, was discovered in the middle of the nineteenth century and was said to have been brought secretly to Wales by Glastonbury monks, for safekeeping, just before the dissolution of the monasteries.[3]

In June 2009 I accompanied three other members of the Powys Society committee and came to Aberystwyth to see the renowned collection of manuscripts, letters and other documents belonging to John Cowper Powys housed in the National Library of Wales.

We were greeted by the principal librarian in charge of the Powys collection. He has the enviable task of cataloguing and taking care of all the Powys items and gave us a preview of some of the documents newly acquired by the library and showed us others that have been in the collection for a long time. It was a privilege and an honour to be allowed access to these original papers.

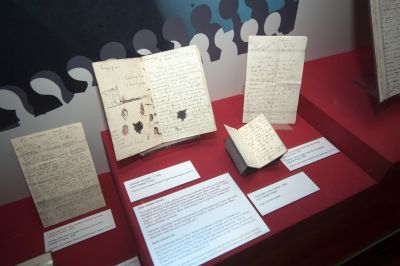

Here were treasures indeed. Laid out on the table we saw the three remaining holograph pages of the manuscript of A Glastonbury Romance. Amongst the many crossings out and substitutions, tucked into a corner of one page were the words that Phyllis, at the last moment, urged JCP to write: “The great goddess Cybele, whose forehead is covered with the Towers of the Impossible, moves through the generations from one twilight to another....” [4] Surely these are the very same pages JCP refers to in his diary on 1 November, 1931: “...after breakfast instead of planting her Bulbs she read the last chapter of my book & told me I must change it & introduce Cybele to whom I have always prayed for it to be good & the Towers of all cults, coming and going – Never or Always.....Think of her having this Inspiration on the day of her going away!” [5]

Here too was an example of JCP’s juvenilia – an incomplete prose tale, written, in 1883, when he was at Sherborne school, in an incredibly neat, small and tidy hand. In this little romance, ‘The Knight of the Festoon”, with its medieval Welsh setting, there is evidence of the influence of his father’s beliefs about the Welsh origins of the Powys family on JCP’s young and fertile imagination.[6] It is, of course, above all, a premonition of greater Welsh things yet to come!

In the morning we joined a public tour of the library and learnt more about the history of the National Library of Wales, its role as one of the major copyright libraries in the UK, and its unrivalled collection of original medieval Welsh manuscripts. Here can be seen not only the Black Book of Carmarthen (the Llyr Du Caerfyrddin),[7] with its Arthurian references and Stanzas of the Graves (the Englynion Beddau), written, it is thought, by a single scribe about the year 1250, but also the Book of Taliesin, the White Book of Rhydderch, The Black Book of Basingwerk, the Hengwrt Chaucer, and Bede’s scientific treatise De natura rerum as well as more modern works by Dylan Thomas and Hedd Wyn.

There are other archival collections here and a wide range of photographs, maps, and pictures with Welsh connections including a valuable documentary source for genealogists and family historians. We were also shown the temperature controlled stacks, which stretch the length of the building, where documents, papers and paintings are all housed.

There was time in the afternoon for us to examine in more detail some of Powys’s manuscripts in the spacious, light, and airy south reading room. The electronic catalogue needs a little getting used to and I had to ask for help to navigate the peculiarities of classification, schedules, hand lists, non OPAQ and ISYS requests. But once you’ve got the hang of it all and received your orders (which are delivered quickly and efficiently) you may spend your time quietly absorbed in the study of original Powysiana.

We looked at all of JCP’s diaries from 1929 to 1960. These simple, plainly covered little books, when opened, reveal an extraordinary world. Every page is covered in Powys’s inimitable handwriting, every available space is used. At first it is hard to work out Powys’s sense of order but soon his style and habits become apparent. Along with all the domestic and personal information there are detailed descriptions of multifarious flowers seen on his regular walks to familiar local places, birds identified, nature’s colours observed, the ever changing light and the vagaries of the weather recorded, including the constantly shifting direction of the wind, reported daily. Yet the wind is never just a wind it is the wind of Hiawatha — Keewaydin or Mudjekeewis.[8] The pages of these little books, like an illuminated breviary, are interspersed with lively and energetic sketches. They are like works of art - a collage of thought and expression. Publication of the diaries can never do justice to the extraordinary visual impression made by the original documents.

I wanted to see the letters to Phyllis Playter. These frank and very personal confessions of love and desire, of loss, and pain, longing, and sensual ecstasy are remarkable documents that deserve to be consulted more often. They are, in many ways, more revealing than the diaries. Written mostly on hotel notepaper, (Powys was writing to Phyllis once and sometimes twice a day) the letters record JCP’s exhausting itinerant life style. The letters reveal the delightful shock of suddenly finding someone new with whom JCP could share his deepest thoughts and intimate feelings. Handling the original copies of the letters is a humbling and moving experience giving insight into JCP’s private world. Will we ever see them, edited , annotated, and published in book form?

There were other treasures to investigate – drafts of poems, including the original heavily worked over holograph of The Ridge, fragments of unfinished works, unpublished short stories and novellas as well as six large volumes containing parts of Powy’s “interminable romance” the” Work Without A Name”.

All too soon our visit came to an end but not before we had made a commitment to return to delve deeper into this astonishing archive of Powys’s works.

Travelling home along sunken green lanes and steep sided, mist filled, valleys I sensed the magnetic quality in the landscape that pulled JCP away from the inspirations of Dorset and Somerset and deeper into his Welsh mountain fastness. Even here on these sunny summer uplands, between Plynlimon and the Berwyns, the towering mountains and hills felt oppressive, hiding perhaps untold mysteries of Pwyll and Priderei of Rhita Mawr, the Cewri, of Brythons and Pelasgians, of ancient battles long since fought and lost, or won, and of Avallach, Nineue and Myrddin Wyllt. From its protective glass case in the National Library, I imagined I could hear, over the sound of modern traffic, the Black Book of Carmarthen uttering its oracular pronouncement:

“ A grave for Mark, a grave for Gwythur/A grave for Gwgawn of the ruddy sword/Not wise (the thought) a grave for Arthur.” [9]

In 2013-2014 NLW mounted a small exhibition of John Cowper Powys books, manuscripts and letters selected from their collection. The exhibition was described by Jacqueline Peltier in Powys Society Newsletter No.80, November 2013.

For more information about the National Library of Wales, opening hours, directions and to search the catalogue of the Powys Collection see: www.llgc.org.uk. Also visit pages on the NLW web site devoted to JCP’s diary for the year 1939 at: http://www.llgc.org.uk/index.php?id=5430