The Dorset Proust

Descents of Memory: The Life of John Cowper Powys, Morine Krissdóttir

A review by John Gray in The Literary Review

It is not hard to understand why John Cowper Powys has never had the

recognition he deserves as one of the twentieth century's most remarkable

novelists. Until he was nearly sixty he earned his living as an itinerant lecturer,

much of the time in America, where he thrilled his audiences by his seeming

ability to transmit, medium-like, the inmost thoughts of the writers he loved.

For a time Powys's electrifying performance as a kind of literary magus

attracted a considerable following. His admirers included some of America's

best-known writers — Theodore Dreiser was a notable supporter, for example — but Powys's method of 'dithyrambic analysis' never caught on. An idiosyncratic

exercise that he described as 'hollowing himself out' so he could become the

writer he was interpreting, it was too obviously adapted to the needs of the

lecture circuit and the quirks of Powys's personality to have any lasting

influence. Powys removed himself further from any kind of critical acceptance

when, in an effort to generate an income that would enable him to give up

lecturing, he published a series of self-help manuals. With titles like The Art

of Forgetting the Unpleasant and In Defence of Sensuality, these forays into

popular psychology were refreshingly unorthodox in their prescriptions for

personal happiness; but they reinforced the perception of Powys as an eccentric

figure flailing about on the outer margins of literary and academic

respectability.

It is not hard to understand why John Cowper Powys has never had the

recognition he deserves as one of the twentieth century's most remarkable

novelists. Until he was nearly sixty he earned his living as an itinerant lecturer,

much of the time in America, where he thrilled his audiences by his seeming

ability to transmit, medium-like, the inmost thoughts of the writers he loved.

For a time Powys's electrifying performance as a kind of literary magus

attracted a considerable following. His admirers included some of America's

best-known writers — Theodore Dreiser was a notable supporter, for example — but Powys's method of 'dithyrambic analysis' never caught on. An idiosyncratic

exercise that he described as 'hollowing himself out' so he could become the

writer he was interpreting, it was too obviously adapted to the needs of the

lecture circuit and the quirks of Powys's personality to have any lasting

influence. Powys removed himself further from any kind of critical acceptance

when, in an effort to generate an income that would enable him to give up

lecturing, he published a series of self-help manuals. With titles like The Art

of Forgetting the Unpleasant and In Defence of Sensuality, these forays into

popular psychology were refreshingly unorthodox in their prescriptions for

personal happiness; but they reinforced the perception of Powys as an eccentric

figure flailing about on the outer margins of literary and academic

respectability.

.jpg) In fact, respectability was never one of Powys's

goals. Both in his writing and his life he scorned conventional standards of

success and followed his own, frequently conflicting inclinations. Easily moved

by sympathy and always recklessly generous with money, he could at the same

time be extremely cunning in satisfying his own needs, which were often

strikingly bizarre or perverse. In his Autobiography (a tour de force of

shameless self-revelation that has been justly compared to Rousseau's

Confessions), Powys wrote that all his life he was pursued by fear — fear of

the world and other people but above all fear of his own manias, 'perpetual

forms of madness' that dogged him throughout much of his life. From his

earliest years Powys believed he possessed ‘some obscure magical power’ to

realise his desires, but many of these involved sadomasochistic fantasies which

filled him with horror and of which he was able to rid himself only after many

years of effort. Describing himself as an ‘anti-narcissist’ who spent his life

running away from himself, Powys escaped from his manias — which included a

loathing of spiders and a horror of his own shadow among many other besetting

anxieties — by employing 'an elaborate psycho-analytical psychi-psychiatry of

my own invention'. Tapping his head on stones and trees, praying to assorted

deities on behalf of suffering creatures human and animal, long peregrinations

with named walking sticks as his regular companions — these and other

compulsive daily rituals allowed him to forget his psychic and physical ailments

(he was plagued by ulcers and chronic constipation) and freed him to write.

In fact, respectability was never one of Powys's

goals. Both in his writing and his life he scorned conventional standards of

success and followed his own, frequently conflicting inclinations. Easily moved

by sympathy and always recklessly generous with money, he could at the same

time be extremely cunning in satisfying his own needs, which were often

strikingly bizarre or perverse. In his Autobiography (a tour de force of

shameless self-revelation that has been justly compared to Rousseau's

Confessions), Powys wrote that all his life he was pursued by fear — fear of

the world and other people but above all fear of his own manias, 'perpetual

forms of madness' that dogged him throughout much of his life. From his

earliest years Powys believed he possessed ‘some obscure magical power’ to

realise his desires, but many of these involved sadomasochistic fantasies which

filled him with horror and of which he was able to rid himself only after many

years of effort. Describing himself as an ‘anti-narcissist’ who spent his life

running away from himself, Powys escaped from his manias — which included a

loathing of spiders and a horror of his own shadow among many other besetting

anxieties — by employing 'an elaborate psycho-analytical psychi-psychiatry of

my own invention'. Tapping his head on stones and trees, praying to assorted

deities on behalf of suffering creatures human and animal, long peregrinations

with named walking sticks as his regular companions — these and other

compulsive daily rituals allowed him to forget his psychic and physical ailments

(he was plagued by ulcers and chronic constipation) and freed him to write.

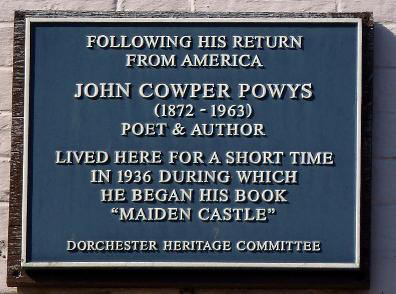

Born in 1872 into a clerical family with literary and aristocratic connections as the first of eleven children, two of whom — Theodore and Llewelyn — also became highly original writers, Powys grew up in the stifling gentility of a Victorian country vicarage. Yet he is in some ways the most modern of writers, taking the dissolution of orderly society for granted and focusing on the shifts and turns of the solitary consciousness with an intensity reminiscent of Proust. As in Proust, Powys's central protagonists are introverted, almost solipsistic figures, who find relief from the sense of being 'contingent, mediocre, mortal' in sudden epiphanies, which they try to preserve in memory. However, whereas Proust's epiphanies occur always indoors in a self-enclosed human world, Powys's were found in the open fields and coastal vistas of his native Dorset — a more-than-human landscape that frames his greatest novels. In Wolf Solent and Weymouth Sands, perhaps the most accomplished of the Wessex series of novels that includes the panoramic A Glastonbury Romance, Powys evokes the floating world of moment-to-moment awareness as found in a collection of characters living on the edges of society, struggling to fashion a life in which their contradictory impulses could somehow be reconciled. The fusion of introspective analysis with an animistic sense of the elemental background of human life which he achieves in these books is unique in European literature.

More than most writers Powys used his memories to create his fictions, but the greatest of these fictions was his own personality. As Morine Krissdóttir shows in one of the most arresting literary biographies in many years, Powys — a ‘sworn hater’ of dreams, which he loathed for the revelations they contained of his only half-successfully repressed obsessions — gave himself over to the conscious creation of a fantasy world in which he could live as the magician he had imagined himself to be as a child. The problem with inhabiting such a dream world, of course, is that it unavoidably contains real people who may not be willing to act the part given them in the fantasy-script. Powys struggled constantly with this fact, which bedevilled his relations with the women in his life. Having made a conventional marriage to the sister of a Cambridge friend, apparently mainly in order to please his family, he went on to spend most of every year in America. It was there that he met the two women he loved — the ‘girl-boy’ Frances Gregg, lover of Ezra Pound and Hilda Doolittle, with whom he began a stormy relationship in 1912, and Phyllis Playter, whom he met in 1921 and who became his lifelong companion.

It was in his relationship with Phyllis — a slight,

nervous, intensely creative woman he called 'the T T', or 'Tiny Thin' — that

the tension between Powys's dream world and the reality of other people became

clearest. Phyllis loved the social and intellectual stimulus of big cities,

while Powys craved a sequestered existence in a peaceful rural landscape that

reminded him of his Dorset home. Krissdóttir writes that Powys viewed Phyllis

as ‘his slender Welsh fairy sylph, his elemental; but elementals are designed

for dancing in the midnight air, not for washing floors’. Certainly the sylph

was Powys's own creation, a figment with only a passing resemblance to his

flesh and blood partner, who found the drudgery and isolation of life with him — first in upstate New York, then Dorset and finally Wales, to which Powys

moved in 1935 and where he died in 1963 — hard to endure. Yet the fact remains

that the two were together for over forty years, during which Phyllis made a

profound contribution to Powys's most innovative and enduring work. In the end

Phyllis may have shaped Powys — the self-styled shaman — more than he shaped

her.

It was in his relationship with Phyllis — a slight,

nervous, intensely creative woman he called 'the T T', or 'Tiny Thin' — that

the tension between Powys's dream world and the reality of other people became

clearest. Phyllis loved the social and intellectual stimulus of big cities,

while Powys craved a sequestered existence in a peaceful rural landscape that

reminded him of his Dorset home. Krissdóttir writes that Powys viewed Phyllis

as ‘his slender Welsh fairy sylph, his elemental; but elementals are designed

for dancing in the midnight air, not for washing floors’. Certainly the sylph

was Powys's own creation, a figment with only a passing resemblance to his

flesh and blood partner, who found the drudgery and isolation of life with him — first in upstate New York, then Dorset and finally Wales, to which Powys

moved in 1935 and where he died in 1963 — hard to endure. Yet the fact remains

that the two were together for over forty years, during which Phyllis made a

profound contribution to Powys's most innovative and enduring work. In the end

Phyllis may have shaped Powys — the self-styled shaman — more than he shaped

her.

Using a mass of new material, Descents of Memory is an inspired study of the tangled and precarious life of an absurdly neglected writer. Unsparing in her description of his exotic array of neuroses and the ways in which he manipulated people to sustain his dream-life, yet full of admiration for his dauntless energy and generosity of spirit, Krissdóttir is clearly deeply torn in her view of the man. She never doubts the extraordinary quality of his best work. Like Powys himself, she sees his vast prose poem Porius — one can hardly call it a novel — as in some sense the culmination of his life's work. For the first time published in the unabridged form Powys intended, this rambling fairy tale of the Welsh dark ages presents Powys's mythic world of animate nature and magical transformations on an epic scale. Written in early old age, Porius is an enchanted labyrinth reminiscent of Finnegan's Wake. For most readers the Wessex novels offer a more accessible way into this Dorset Proust. Seeking a sort of salvation in distilled sensation, Powys turned to memory in an attempt to master time. Whether or not he achieved any kind of personal redemption (Krissdóttir's biography suggests otherwise), he came as close as any modern writer to capturing the inner flux.